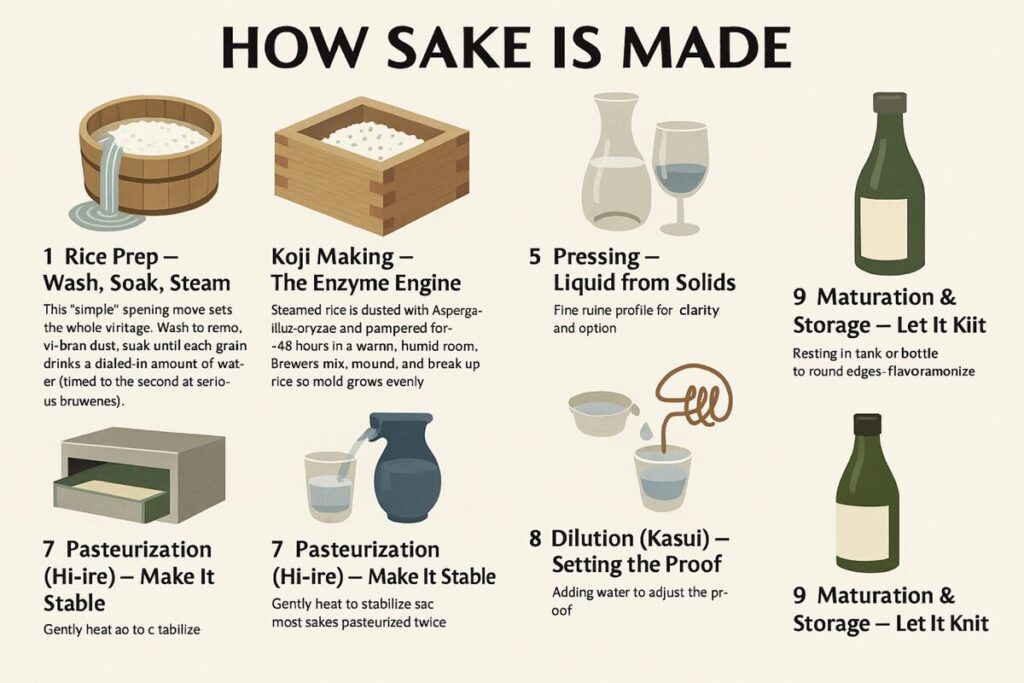

How Sake Is Made A Simple Guide

Rice Preparation Wash Soak Steam

This first move sets the whole vintage. Washing removes bran dust. Soaking is timed so each grain absorbs a precise amount of water, down to the second in serious breweries. Steaming, never boiling, fixes the texture that will steer everything that follows. The exterior must hold its shape in the tank and the center must offer itself to enzymes and yeast. Tiny differences here can be heard all the way in the glass.

Koji Making The Enzyme Engine

Steamed rice is inoculated with Aspergillus oryzae and tended for about 48 hours in a warm, humid room. Brewers mix, mound, and break up the rice so the mold grows evenly. Koji converts starch into sugar, which becomes food for yeast. If wine begins with grape juice and yeast, sake begins with starch that is first turned into sugar, then fermented. Koji is the hinge that makes that chemistry sing.

Yeast Starter Shubo Raising the Culture

In a small tank, water, koji rice, plain steamed rice, and yeast are combined to build a strong and stable population. A protective acidity keeps wild microbes out. In the classic kimoto or yamahai approach, that acidity develops slowly and often yields richer, wilder characters. In the quick sokujo method, it is added at the start, which produces a cleaner, tauter profile.

Main Mash Moromi Three Steps to Cruise Control

With the starter ready, everything scales up in three additions known as sandanjikomi. The staggered build keeps sugar, temperature, and alcohol in balance while two processes run in parallel. More starch becomes sugar, and that sugar becomes alcohol. Cooler and longer ferments chase perfumed ginjo notes. Slightly warmer runs favor rounder, rice-forward flavors. Expect a few calm weeks in the tank.

Pressing Liquid from Solids

When fermentation has done its work, the sake is separated from the lees, or kasu. Method shapes style. Modern membrane presses are clean and efficient. The box press, or fune, is gentler. Gravity-only shizuku drips taste silken. Even one pressing has chapters. Arabashiri is the lively first run. Nakadori or nakagumi is the prized middle cut. Seme is the firmer tail.

Clarifying and Optional Charcoal Filtering Tuning the Tone

Fining brings clarity and allows small adjustments to the profile. Activated charcoal can lift out color and certain aromas. Skip it and you have muroka, often more vivid and textural. There is no dogma here, only house style.

Pasteurization Hi-ire Make It Stable

A gentle heat treatment quiets enzymes and remaining microbes. Most sakes are treated twice, once after pressing and once before bottling. One-time versions exist, such as namachozo or namazume, while fully unpasteurized namazake tastes electric and demands strict cold storage.

Dilution Kasui Setting the Proof

Tank strength often sits around 18 to 20 percent alcohol by volume. Adding brewing water brings it to table strength in the mid-teens, where balance clicks into place. If the label reads genshu, it is undiluted, bigger, warmer, and more powerful.

Maturation and Storage Let It Knit

Resting in tank or bottle lets edges round and flavors harmonize. Some breweries ship young for snap and lift. Others hold cool for months. A few age for years into koshu that turns amber, nutty, and complex. Rankings can be fascinating, but behind each tidy word on a label lies this entire sequence of choices, each one audible in the glass for anyone who cares to listen.

What “Polishing” Really Means

When people think of sake, they often picture a small ceramic carafe, maybe steaming gently in a corner sushi bar beside a plate of tempura. It feels familiar and almost cozy. What most people do not know is that this centuries-old drink has its own ladder of prestige, a hierarchy as intricate as French wine appellations or Scotch classifications. At the center sits one plain little number, the seimai buai, the rice-polishing ratio.

Polishing here has nothing to do with shine. There is no buffing and no gleam. It is about subtraction. Imagine a grain of brown rice. The outer layers hold proteins and fats, while the inner core is almost pure starch. A label that reads “50%” tells you that half of the grain has been milled away. What remains is the pale, starchy heart. Lower numbers mean more of the exterior is removed. Rough edges fall away. Earthiness recedes. The result can be lighter, more transparent, often more aromatic. At times the nose is so floral you could mistake the glass for a white Burgundy rather than a drink made from rice and water.

That quiet ratio is a key to sake’s alchemy. It explains how rice and water, two of the simplest ingredients, can become something that shares the stage with the world’s most elegant wines. The art lies in knowing how to read the numbers.

Eight Shades of Sake

The sake world sorts itself into eight broad styles. They depend on three levers. How far the rice is polished. Whether the brewer adds a touch of distilled alcohol. The general flavor profile that follows from those choices. Picture a ladder. Everyday, more rustic sakes at the lower rungs. At the top, liquids that feel crystalline, ethereal, and precise.

| Rank (Description + Pairing Examples) | Name | Typical Polishing Ratio | Added Brewer’s Alcohol | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ultra Premium (gift or special celebration) Sushi platter, sashimi (white fish), kaiseki-style appetizers |

Junmai Daiginjo | 50% or less (highly polished) | No | Extremely aromatic and delicate; the quintessential premium sake. |

|

Premium (special occasions and fine dining) Mixed sashimi, grilled sea bream, French-style seafood |

Daiginjo | 50% or less | Yes | Close to Junmai Daiginjo but lighter due to added brewer’s alcohol. |

|

Elegant Food Pairing Sake Tempura, braised fish, Japanese-style pasta |

Junmai Ginjo | 60% or less | No | Floral aroma with rice umami; a popular food-friendly choice. |

|

Aromatic Everyday Treat Grilled mackerel, miso-marinated chicken, light cheese board |

Ginjo | 60% or less | Yes | Aromatic and crisp; great value in the ginjo style. |

|

Crafted Daily Sake Beef sukiyaki, teriyaki salmon, miso-glazed vegetables |

Tokubetsu Junmai (Special Junmai) | 60% or less or special method | No | Deeper flavor; a more crafted take on junmai. |

|

Light and Smooth Daily Sake Yakitori (soy glaze), agedashi tofu, fried chicken |

Tokubetsu Honjozo (Special Honjozo) | 70% or less or special method | Yes | Clean, smooth taste with a restrained aroma. |

|

Rustic Home-Style Sake Nabe (Japanese hot pot), simmered vegetables, assorted pickles |

Junmai | No fixed regulation | No | Showcases rice umami; a natural style of sake. |

|

Everyday Table Sake Grilled fish set meal, izakaya-style appetizers, simple sushi rolls |

Honjozo | 70% or less | Yes | Light and easy-drinking; ideal for everyday meals. |

At the Pinnacle (Junmai Daiginjo)

Here is the crown jewel. The rice is polished to 50 percent or less, which means more than half of every grain has been milled away. Making it demands patience, money, and near-obsessive care. Nothing is added beyond rice, water, and koji. No shortcuts.

The result is a perfume that is vibrant yet restrained, and a taste that unfolds like silk sheets drawn back one by one. It is the bottle you bring to a wedding, or pour when you want to mark something that matters.

Balanced and Versatile (Junmai Ginjo)

At 60 percent or less, Junmai Ginjo sits in a softer place on the ladder. It balances the gentle sweetness of rice with the bright fragrance that comes from ginjo brewing. It is elegant and flexible. It pairs as easily with sashimi as it does with Italian pasta or a French seafood stew. Add a touch of distilled alcohol and you have Ginjo, which is lighter and crisper, a little more refreshing, the kind of sake that cuts cleanly through a summer evening.

Aromatic and Airy (Daiginjo)

Daiginjo stands close to Junmai Daiginjo but with a twist. A small addition of distilled alcohol lifts the aromas, gives the drink a buoyant feel, and makes each sip seem almost weightless. It remains a luxury, but one that greets you with a wink rather than a bow. It pours as naturally beside oysters as it does with a clever appetizer.

Why Junmai Ginjo and Daiginjo Matter

Both belong to tokutei meisho-shu, the family of special-designation sakes. What they share is a low polishing ratio. Remember, the smaller the number, the more of the grain has been removed. Strip away proteins and fats from the outer layers and you get something cleaner, clearer, and brighter. A sake that gleams in the glass and speaks in a finer register.

Sake looks simple on paper. It uses three ingredients (rice, water, and kōji mold), yet no two breweries make it in quite the same way. The smallest extra step can draw out a delicate change in flavor. Choosing a bottle can feel like tiptoeing through a library where every cover is plain white but each book tells a different story once you open it.

To bring some order to that variety, sake is ranked by how much of the rice kernel is polished away. Seimai-buai, the polishing ratio, tells you what percentage of the grain remains. If you see 60 percent, it means 40 percent has been milled off. Seihaku-ritsu, the polishing rate, flips the view: 60 percent means 60 percent has been removed, leaving 40 percent behind. High-polish sake, once a classic badge of prestige, grinds the grain down to its starchy heart and often yields an ethereal, perfumed style. Tastes change. Low-polish sakes, which keep more of the grain, are enjoying their moment. Some breweries even work with unpolished brown rice, a choice that feels both rebellious and old-fashioned.

Polishing never tells the whole story. Each brewery guards its own methods, especially in the way it nurtures kōji. These tiny green spores (Aspergillus oryzae) are the real alchemists. They turn starch into sugar and lay the groundwork for yeast to do its work. The style of kōji-making involves temperature curves, humidity control, and how often the rice is stirred, and these choices can tilt a sake…

There is another twist you will not find on most labels: the way sake’s nutrition comes together. Unlike wine or beer, sake brings a bouquet of amino acids and organic acids produced during kōji-driven fermentation. More amino acids may offer small benefits for metabolism and fatigue recovery. Ferulic acid and other antioxidant compounds suggest a measure of protection against lifestyle-related ailments.

Brown-rice sake goes further because the outer layers hold B vitamins, minerals, fiber, and polyphenols that can survive the brewing process. Think of it as sake with a whole-grain edge, more rustic on the palate, earthier on the nose, and a little bolder in its health claims as well. White-rice sake may be easier to digest and typically drinks with a smoother line. Different bodies and different moods will find their match.

If all this polishing sounds wasteful, it helps to know that the mountain of rice bran does not go to waste. It is repurposed into rice crackers, cakes, noodles, and gluten-free flours that slip into breads and pastries. What does not end up in your glass may still land on your plate. The next time you pour a cup, remember that behind that clear liquid stands a world of invisible decisions—when to stir, how much to shave, whether to chase refinement or lean into boldness. Sake may rest on three ingredients, but it is defined by choices, and that is what makes the hunt for the right bottle half the fun.